Kingston-upon-Hull, or Hull as it is known to the locals and non-locals alike, lies on the north bank of the river Humber in what was once the wapentake of Harthill (Hunsley Beacon division), part of the historical East Riding of Yorkshire (see maps in Introduction). It is not mentioned in Domesday for the simple reason that it did not exist under that name at the time of the survey. It was over a century later that an uninhabited part of the hamlet of Myton, in the parish of Hessle, became the outlet for the wool produced by the Abbey of Meaux and at the same time the nucleus of the future city. From its modest beginnings on the west bank of the river Hull, it today encompasses Drypool, Marfleet, Sculcoates and Sutton, along with parts of the surrounding ancient parishes.

In 1086 Myton was in the hands of Ralph de Mortimer and considered partially waste. By the time William d’Aumale, Lord of Holderness, had founded the Abbey of Meaux in 1151, the land had passed to Robert de Meaux, and it was he who granted four bovates to the abbey along with two-thirds of his fee of the Wyke of Myton. By c1200 the abbey had acquired the rest of the Wyke of Myton and had founded a town there, initially known as Wyke upon Hull. This situation was to last until 1274 when Aveline de Forz died and, as the last holder of the lordship of Holderness, her lands reverted to the Crown. By then Edward I, intending to develop a port in the north of England suitable for commerce and to act as a supply base for his Scottish campaigns, already had his eye on Wyke. The nearby ports of Hedon and Ravenser were considered unsuitable, the former being only accessible up a creek prone to silting, and the latter built on shifting sands risking destruction by the sea. The king therefore lost no time in acquiring Wyke upon Hull from the abbey in return for compensation, renaming the town Kingston upon Hull.

By 1299 Hull had already gained sufficient status to be declared a borough by royal charter and be granted various liberties, but it was to remain beholden to the king over the following century, supplying ships, men and provisions during the ongoing campaigns against the Scots and for the wars against France. However, by the end of the 1300s the town was asserting its independence and in 1440 obtained county corporate status. Its relationship with the Crown during this period was ambivalent, as shown by its vacillating support for the houses of York and Lancaster during the Wars of the Roses. This attitude prevailed towards the Pilgrimage of Grace in the following century, and Hull was pragmatically accepting the reformist teachings by the time of Henry VIII’s visits in the mid 1500s. Good relations with the king were consolidated when he reinforced the town’s defences by building blockhouses on the east bank of the river Hull, along with the castle. Ironically, it was the recently dissolved Abbey of Meaux that provided some of the materials for the castle, which was later used to imprison recusants. During the Civil War of the mid 1600s Hull defied the reigning monarch, when its Parliamentary governor Sir John Hotham refused entry into the town to Charles I, thus depriving the king of access to Hull’s large arsenal.

The Civil War marked an adverse blip in Hull’s hitherto prosperous trade with the northern European ports, mainly the export of cloth and the import of corn, along with the import of wine from southern Europe. By the late 1600s Hull’s defences had fallen into disrepair, an inspection revealing that the north blockhouse was beyond salvation and the south blockhouse needed extensive repairs. It was decided to strengthen the latter and incorporate it with the castle in a triangular fortification which became known as the citadel and which was to survive until the mid 1800s. However, more radical measures were needed on the west bank, where the moat had silted up. At the same time Hull’s trade was expanding, thanks to easier access provided by a network of rivers and new canals, and the staithes on this bank used for the loading and unloading of goods were proving inadequate. Against much time-consuming opposition from the owners of the lucrative staithes, it was finally decided to demolish the town walls and replace them with docks. The first to be built in 1778 was simply known as The Dock, later renamed Queen’s Dock, followed in the early 1800s by Humber Dock and Junction Dock, later renamed Prince’s Dock. However, in the meantime the ports of Grimsby and Goole had taken advantage of Hull’s dithering, offering ships shorter turn-arounds at lower prices. By the mid 1800s the amount of goods passing through the port of Hull had declined, due to a great extent to competition from its neighbours.

|  |  |

The opening up of the trans-Atlantic trading route through Liverpool and London and Bristol’s links with India and China meant that Hull was faced with more competition. Furthermore, the advent of the railways, offering quicker transport than via the inland waterways, only served to emphasise Hull’s isolation on the north bank of the Humber and its lack of rapid access to the south. Grimsby again took advantage of the situation. But Hull managed to fight back by diversifying its trade to include the export of finished products and the import of raw materials and consumer goods, and by developing its industrial base to encompass seed-crushing, grain-milling and iron shipbuilding. Hull had been a whaling port since before the end of the 16th century; it now turned to trawler fishing in the vast spawning grounds of the North Sea. By 1870 Hull was considered Britain’s third port, thanks mostly to the fishing industry and its ancillary trades; this was given a further boost in the 1890s with the switch from sail to steam. Hull also benefited as a transit port for emigration from Scandinavia and Eastern Europe to America and the export of coal from the South Yorkshire coalfield. The culmination of its achievements was the granting of city status in 1897.

Hull’s prosperity peaked in the years leading up to the First World War. The conflict badly affected overseas trade, cutting off links with Germany completely and severely curtailing those with Russia and the Baltic countries. Hull had hitherto depended on a large unskilled workforce to handle its goods and to keep its industry operating, but with the cessation of hostilities, mechanisation was introduced, leading to mass unemployment. In the 1920s and 1930s Hull came to be known as “Britain’s Third and Cheapest Port”. The situation had hardly eased before hostilities broke out again in 1939, when Hull became the target of widespread bombing. Most of the city centre was destroyed and 95% of its houses damaged or obliterated, making it the second most severely bombed British city or town after London during the Second World War.

The damage caused by the war was an opportunity to carry out a comprehensive programme of town planning, though slum clearance did not begin before 1952 owing to the shortage of existing houses. The import trade was subject to national restrictions and, although this did not include grain imports, these declined because several flour mills had been damaged or destroyed. On the other hand, exports managed to recover and eventually exceed their 1938 levels. It was the fishing industry and its ancillary trades that put Hull back on its feet. The beginning of 1960s saw the development of the deep-sea stern trawler, powered by diesel-electric motors, with the capacity to freeze up twenty-five tonnes of fish each day. By the 1970s trade had picked up again and large numbers of dockers found work in the port. But it was not to last: modern advances like the shipping container, the fork-lift truck and privatisation put an end to unskilled work, only to be compounded by the Anglo-Icelandic Cod War of 1975-1976, when Iceland extended its fishing limits, prohibiting foreign vessels form fishing in its waters. These were the main factors that set in motion Hull’s decades long economic decline. It was to be further impacted by the financial downturn of 2008.

2008 was also the year when Hull City, the local football team, was promoted to the Premier League and by October was number three in the table, triggering a surge of optimism in the city. In 2013 Hull was given another boost by being nominated UK’s City of Culture for 2017, and in 2014 its team reached the FA Cup Final. 2014 was the year when the German engineering giant Siemens and Associated British Ports announced a £310m investment in a wind turbine production and service plant based at Alexandra Dock. Further investments were promised: £200m by Reckitt’s Healthcare in its Centre for Scientific Excellence and £27m by Croda in its manufacturing facility, and a C4Di technology incubator was built on the premises of the former fruit market. In 2016 the city registered its strongest growth rate, 43% above the national level, and historically low unemployment levels. So Hull is back on its feet again and today its future looks bright.

The earliest mention of the place of worship which took the name Holy Trinity was between 1197 and 1210. A chapel of ease belonging to the parish of Hessle stood there when the Abbey of Meaux acquired Wyke. It was subsequently dismantled by the monks, most likely to make way for the church, which was established c1285 but remained dependent on the mother church in Hessle. It was used as the parish church, although its status as such was not recognised until 1548, and in 1661 an act of parliament finally made it “distinct and separate”. Holy Trinity church is cruciform, with a central tower and is the largest parish church in England in terms of floor area. The transepts are the earliest part of the building, begun in the last decade of the 13th century, but show signs of an earlier building. The chancel was erected during the 14th century. Both transepts and chancel are constructed of brick – some of the earliest medieval brickwork in the country – and covered with stone dressings. Work on the nave began towards the end of the 14th century, and the tower is thought to have been started in the 15th. The latter was built in three stages and not completed before the early 16th, thought to be due to the unstable nature of the boulder clay on which Hull is built. Traces of several chantry chapels on the south side of the nave and chancel can still be seen, now converted into vestries and burial vaults. Various repairs and alterations were carried out in the late 16th century, and the building underwent a lengthy period restoration from 1861 to 1878. The church was largely spared serious damage during the wars of the 20th century, although the east window was destroyed during the First World War. Holy Trinity was given Minster status in 2017.

A Henry Pickering appears in the parish registers of Holy Trinity in the 1560s and, though the available information is sketchy, he seems to have had three wives and about ten children. He and his assumed brothers, Thomas and Robert, flourished for a couple of generations, but either died out in the male line or moved to other parishes. A Puckering family also made an appearance in the mid 1650s but died out in the male line within a generation. Many Pickerings are recorded over the next two and a half centuries, including members of the Pickerings of Chollerton, Driffield, Foston on the Wolds, Holderness, Hull 1, Hull 2, Hull 3, Kilnwick 1, Kilnwick 2, Melbourne and Skeckling cum Burstwick.

The early history of the church of St. Mary mirrors Holy Trinity’s: it also started life as chapel of ease, its mother church being that of the parish of North Ferriby, though it was first documented much later, in will dated 1327. By 1333 St. Mary’s had become the parish church in all but name for the area of Lowgate, but it was not until 1868 that it was was officially separated from the mother church. The church building is made up of six bays with aisles, the three eastern bays being used as a chancel and the three western as a nave. Its other features include a western tower, a south porch, and a vestry. In 1333 the church was described as newly built (de novo constructa), though a study of its architectural characteristics points to reconstruction having taken place over a long period, beginning in the east towards the end of the 14th or early in the 15th century, and culminating with the completion of the west tower the early 16th century. A widely held belief, described here by Abraham de la Pryme, states that:

In ye year 1538 when that Sacrilegious & Arbitrary Prince King Hen. ye 8 came to this Town & Recided somewhile at his Pallace or Manour Hall here He caused ye Great Body of ye sayd Church of St. Mary’s & ye Great Steeple thereof to be all pulld down to ye bare Ground for ye enlargement of his Manour & converted all ye Stone & woodwork thereof to ye Walling of ye same and ye use of ye Blockhouses that he then caused to be made on ye Garrison side then called Dripool side.

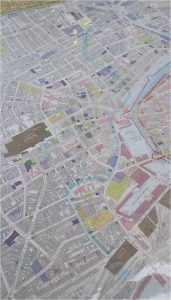

Some credence is lent to the belief if one examines the ancient plans of Hull. The plan dated c1540 shows St. Mary’s with a tower as an integral part of the building, but by the mid 1600s it no longer exists. The present tower, dated 1696, appears to be add-on, built on top of an already existing pavement with a walkway through its base. A number of ecclesiastical stones were discovered in the walls of the north blockhouse, when they were finally taken down in 1802, also a sculptured stone was found during the digging out of Victoria Dock in 1850, and again more stones of a similar nature were revealed in the magazine, which had been built on the remains of the old castle, when the citadel was demolished. As seen above, material from the dissolved Abbey of Meaux was used in the building of Hull’s eastern defences. It is therefore possible that several edifices were the sources of the stones.

|  |  |

The parish registers of St. Mary’s are more forthcoming than those of Holy Trinity, and it is reasonably safe to assume that the first Pickering male to appear is John the son of Thomas of the 17th generation of the Pickerings of Holderness, who was baptised in Bishop Burton in 1565 and later moved to Hull. In 1587 John was a witness to the purchase of a close near the north blockhouse in Drypool by John Cavert, a glover, to whom he was probably apprenticed as he became a glover himself. He married his first wife in 1590 who bore him six children, all baptised in the church of St. Mary. She died in 1601, John married three more times, though no more children were baptised, and he died a widower in 1629. In the decade before his death he bought and sold several properties in Hull, Drypool and Sutton. He left a share of his dwelling house in Bishop Lane Staithe with access to the river Hull to each of his two younger sons Joseph and Thomas, on condition that they make a weekly payment of six pence to their brother William who, as the first born, had already received lands in the parish of Drypool. Joseph and Thomas were also given meadows in Arnescroft and Kirkefield in Drypool. John Pickering’s family seems to have died out in the male line, so I am one of many who have his brother Anthony of Hedon to thank for founding the Pickerings of Holderness. Other Pickering families who celebrated their life events at St. Mary’s were the Pickerings of Chollerton, Hull 2, Lincolnshire and Preston.

|  |  High Street end, 2025 |  © History of Bishop Lane / Staithe |  River Hull end, 2025 |

Drypool before the Conquest was largely fenland, badly drained and liable to flooding, but by the time of the Domesday survey flooding had gradually raised the level, making cultivation and human occupation possible. The fields which later became pasture for the cattle and sheep of Drypool and Southcoates required constant protection from tidal surges. Drainage dikes were dug along the Humber estuary and the banks of the river Hull were reinforced by sluices, known locally as clows or cloughs, to stop salt water entering the dikes. However, Drypool and the low-lying areas of Hull were constantly at risk of flooding until the River Hull tidal surge barrier was opened in 1980.

Two manors were recorded – Drypool and Southcoates – its tenants in chief being the Archbishop of York and William I’s relative and companion Drogo de la Beuvrière, but their lands were still considered waste twenty years after the Conquest. Both manors, along with their chapels, belonged to the parish Swine until the mid 1600s when Drypool cum Southcoates became a separate parish. The demesne lordship was held by the Sutton family from at least 1227 until the death of Sir Thomas de Sutton shortly before 1389. Thereafter and and up until the 18th century Drypool and Southcoates was divided among numerous landlords, passing through the hands of several families associated with the Pickerings like the Alfords, Broomfleets, Bygods, Constables, Hastings, Smethleys, St. Quintins and Ughtreds.

Although not mentioned in Domesday, a church or chapel dedicated to St. Peter existed at Drypool in the 11th or early 12th century; it is first documented in 1226. The plan of Hull and Drypool of c1540 shows the church building consisting of a broad nave with south aisle, a small chancel and a crenellated tower, the church and graveyard surrounded by a crenellated wall. The church was said to be in a ruinous state by 1428 and repairs were undertaken over the ensuing centuries, but it was only in 1822 that it was dismantled and rebuilt. The windows and arches of the old structure were preserved, along with the same patterns and mouldings. The reconstruction process revealed a round recessed north doorway of five orders from the 11th or 12th century, 14th century windows in the north wall of the nave and chancel and in the tower and a 15th century window of three lights in the south wall of the nave. The roofs, which had originally been pitched, had later been flattened and the tower truncated. The rebuilt church which was finished in 1824 was larger, with galleries on three sides. It had a four bay nave, a chancel in the form of a semi-hexagonal apse and a four stage west tower with a parapet and pinnacles, the whole cement rendered. The font probably came from the old church, and an organ was later installed. The church was destroyed by bombing in 1941 during the Second World War and was never rebuilt, probably because a new church, dedicated to St. Andrew, had already been built in 1878 and had become the parish church, while St. Peter’s had become a chapel of ease. In 1959-60 both the churchyard and cemetery of St. Peter’s were made into gardens by the corporation, the only items remaining being a few gravestones set against the remains of the old church wall.

from a lithograph |  unknown source |  © Paul Glazzard, 2007 |

There was also a chapel at Southcoates, dependent upon Drypool, the property of the lords of Sutton before coming into the possession of Sutton College shortly before the Dissolution. It seems to have been suppressed at the same time as the college in around 1547.

As seen above, well before Drypool and Southcoates were built, the land was made up of fields given over to farming. There were four fields in total: Arnescroft, Kirkefield, Middle Field and West Field. By the time of his death in 1629 John Pickering of St. Mary’s parish, Hull, (see above) had acquired meadows in Arnescroft and Kirkefield, alongside those belonging to several prominent local families, like the Constables, the Hildyards and the St. Quintins. John’s son William was the first recorded Pickering in the parish registers of Drypool. He married there, became a church warden, had his children baptised and was buried there, though the rest of this branch remained in Hull. It was Frederick Pickering, a direct descendant of this John’s brother Anthony of Hedon, the founder of the Pickerings of Holderness, who was the next person from this branch to live in Drypool and have his ten children baptised there from 1879 to 1900. In the mid 1800s George Gilchrist, a member of the Gilchrist family of Etal, Northumberland, and the uncle of Frederick Pickering’s maternal grandmother, built his business premises in Drypool, on the reclaimed lands lying beside the river Hull known previously as the Growths and later the Groves. Other families who celebrated their life events at St. Peter’s were the Puckerings of Flamborough and Bempton and the Pickerings of Wawne.

Marfleet is separated from Drypool by the river Wilflete, now known as the Holderness Drain and, like its neighbour, was built on low-lying marshy ground, often subject to flooding. Held by Lord Morcar before the Conquest, it too was granted in 1086 to William I’s relative and companion Drogo de la Beuvrière, who owned most of Holderness. The Lords of Holderness remained its tenants in chief until the late 1200s, their under tenants being local families, including the Marfleets and the Rooses; thereafter it passed through various hands.

The chapelry of Marfleet depended on its mother church at Paull until the early 1700s, when it was described as a parish church. No image of the medieval building has come to light, and in 1793 it was rebuilt at the parishioners’ expense. The new church, dedicated to St. Giles and consisting of a nave with Gothic windows and a cupola over the west gable, was in bad repair by 1865, and was replaced in 1884 by its third reincarnation, designed in the Geometric style.

The only Pickering associated with Marfleet is the carver, Ernest Pickering, whose work can be seen in the church: the litany-desk, the reredos, the memorial to those killed in the First World War and the sanctuary panelling erected in memory of Rosamond Brittan. No connection with an established Pickering family has yet been found.

|  |  |  |

Sculcoates is believed to be a Viking name meaning “Skuli’s cottages” but, if they existed at the time of the Domesday survey, they did not warrant a mention. Perhaps it was only in the 1100s that silting on the west bank of the river Hull had raised the level of the land and, combined with drainage, rendered the mud flats more suitable for the building of cottages. Whatever the reason, the first record of Sculcoates seems to have been in 1232, when the church was mentioned. A century later the parish was still small, sparsely populated and also poor, contributing only £1 14s in rural tax in 1334. By the 1600s about a dozen houses lay between the Charterhouse and St. Mary’s Church, and a survey of 1743 shows that Sculcoates had remained poor, as most families were found to “have but one low room” or “live in a chamber”. The village was predominantly agricultural until the late 1700s when industries were established beside the river, and it was only in the early 1800s that its population began to rise rapidly. This brought about a change in the character of the parish, though some fields remained and were still used for farming as late as the 1750s. There were market gardens in the early 1800s.

The first tenant in chief of Sculcoates, the Archbishop of York, was mentioned in the 1200s and the parish probably remained in the tenure of the successive holders of the office until the Dissolution. The first holder of the manor was Benet de Sculcoates. By 1221 it had passed to Robert de Grey, Benet’s nephew by marriage, and Sculcoates was to remain in the hands of the Greys until the late 1300s. There was a manor house by 1346, when John Grey received a licence to fortify it. In 1376 it passed to John de Neville, thereafter to Michael de la Pole, the founder in 1377 of the Carthusian Priory, to whom he granted the manor two years later. The manor passed to the Crown at the Dissolution.

The first church in Sculcoates stood by the river Hull on what became known as Bankside. A drawing dated c1725 shows the medieval church dedicated to St. Mary as a small, simple building with a nave, a chancel and a turret for the bell. By 1743 it was in need of repair, and in 1759 it was decided to build a larger church on the same site, to meet the needs of the growing population. The style of the new church was classical with a touch of sober rococo gothic, but its appearance was to be considerably altered in the 1820s and again in the 1860s. In the meantime the area of Sculcoates lying to the south west of St. Mary’s was being developed, and it was decided that a new church was needed to serve it. The church of All Saints was built in Margaret Street, consecrated in 1869 and became the parish church, St. Mary’s having become a chapel of ease by 1873. This heralded its final demise, as in the early 1900s there were plans to close it and replace it. A new brick church in the Early English style was built in neighbouring Sculcoates Lane and became known as new St. Mary’s. Many of the fixtures and fittings of old St. Mary’s were transferred to it, including several monuments and the font. The old church survived for a number of years but was finally demolished in 1906, though the tower would remain standing into the 1950s.

|  |  |  |

The parish registers for St. Mary’s started in 1538, but the first identified Pickering was baptised as late as 1803: Nathan of the Pickerings of Malton. The other Sculcoates Pickerings mostly belong to the vast Pickerings of Holderness family, including my father, John Leslie, who was a boy scout attached to All Saints’ church. It was his great great grandfather Richard Hazmalanch who was the most closely associated with Sculcoates; his is one of the rare gravestones still standing in old St. Mary’s cemetery. Offshoots of Holderness family who celebrated some of their life events at St. Mary’s were the Pickerings of Barmston, Preston, Wawne and Welwick. Alongside them were the unrelated Puckerings of Flamborough and Bempton and the Pickerings of Auckland St. Andrew, Chollerton, Driffield, Hull 1, Hull 2 and Kilnwick 1.

Sutton on Hull or Sutton in Holderness is recorded as Sudtone in Domesday. “South Farm” itself stood on a long, low ridge of dry ground, running roughly from north west to south east, surrounded by extensive meadows and carrs. The manors owned by Earl Tosti and Grimkel before the Conquest were in the hands of Drogo de la Beuvrière by 1086, and the manor owned by the Canons of St. John of Beverley and the Archbishop of York devolved to the office of the archbishop alone. By the mid 12th century the demesne lordship was in the hands of the Sutton family, which held it until the death of Sir Thomas de Sutton shortly before 1389. Thereafter its ownership followed that of Drypool and Southcoates.

Sutton was one of the larger parishes of Holderness and remained agricultural until the 18th century except in the southernmost area, which developed along with Drypool. The recorded population in 1086 was eighteen, probably representing the number of households. There were fourteen taxpayers in of 1297, paying a total of £1 6s, and in 1377 as many as 299 adults paid the poll tax. In 1743 there were about 80 families, and by the end of the century the growth of Hull was beginning to affect Sutton. In 1801 the population of the parish was already 1,569, had almost doubled in the following decade, then steadily increased to 7,783 in 1851. However, the development did not involve industry but the building of houses for the wealthy inhabitants of Hull; by the following year Lambwath House, Sutton House, Sutton Grange, Tilworth Grange and East Mount, along with their extensive grounds, had all appeared. In 1901 the population stood at 15,043.

A chapel at Sutton, dependent on the church of Wawne, was first mentioned by William d’Aumale in c1160 when he confirmed his father’s gift of Wawne church to the abbey of St. Martin d’Auchy in Aumale, Normandy. However, William had also granted the same church to the abbey of Meaux in c1150, which led later to a dispute that was only resolved when the Archbishop of York annexed it in 1230. There was no formal separation of the chapel from the mother church, nevertheless it was regarded as a rectory in 1291. In 1346 the lord of the manor, Sir John de Sutton jr., was licensed to found a college at Sutton for which the chapel was appropriated. By then the chapel was in a dilapidated state and extensive rebuilding was undertaken between 1347 and 1349. Sir John funded the building of the nave in locally produced brick, while the chancel was remodelled or rebuilt of stone from outside the area and brought up the river Hull to Stoneferry, thence via the Antholme dike (later the Hantom drain) to Sutton. Once completed the new church was consecrated and was to remain a collegiate church dedicated to St. James the Great until its suppression in 1547.

Over the 300 years following the suppression of the college, the church gradually decayed and was periodically repaired or patched up. Its brick nave with stone dressings, designed originally for the use of the villagers, was supplemented by aisles of four bays, but the pitch of its roof was lowered and its external walls covered with rough cast. Its disproportionately long stone chancel, where the priests of the college had held their daily services, was also cut down, destroying its arch and tracery, along with the pointed arch of the east window. Some windows also lost their tracery and were blocked. In 1785 the first of the galleries was erected, positioned between the arches of the nave and the side walls, and pierced for the insertion of windows, forming a kind of clerestory. The Victorians undertook major restoration work starting in 1866. The galleries were removed, and the chancel arch raised again, along with the floor. The east and west windows were reconstructed, and the imposing brick columns in the nave replaced by stone piers.

|  |  |  |

The most striking feature of the church is the fine stone table tomb and effigy of the founder of the college, depicted clad in the armour he wore in 1346 at the Battle of Crécy, which until the Victorian restoration stood in the centre of the chancel, but now stands on the south side of the choir.

The Pickerings of Auckland St. Andrew, Malton, Wawne and Welwick celebrated some of their life events at Sutton church, but it was Benjamin Pickering of Melbourne in Derbyshire who made Sutton his residence, having made his fortune in Hull as a draper and seed crusher. Towards the end of the 19th century he bought Bellefield House, built in 1815 by John Hipsley, a fellow draper. Pickering “enlarged and beautified” it, adding a tower, a conservatory and a billiard room. He lined the dining room with mahogany panelling and hung portraits of the kings and queens of England from William I to Victoria on the walls. The house was demolished in 1965.

Sources:

Hull:

https://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ERY/Hull

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingston_upon_Hull

https://opendomesday.org/place/TA0928/myton

A History of the County of York East Riding: Volume 1, the City of Kingston Upon Hull: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/east/vol1

History of the Town and Port of Kingston-upon-Hull: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.319510020476979&seq=9

Chronica monasterii de Melsa, vol. 1, p.168: https://archive.org/details/chronicamonaste01thomgoog/page/168

The River Hull’s secret past that changed the city forever: https://www.hulldailymail.co.uk/news/history/river-hulls-secret-past-changed-1558683

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hullshire

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hull_Castle

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fortifications_of_Kingston_upon_Hull

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cod_Wars

To Hull and back: the rebirth of Britain’s poorest city: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/sep/11/-sp-to-hull-and-back-the-rebirth-of-britains-poorest-city

Raising Hull: how culture and investment are resurrecting an English city: https://www.fdiintelligence.com/content/feature/raising-hull-how-culture-and-investment-are-resurrecting-an-english-city-70100

Hull’s Economic Strategy 2021-2026: https://www.hull.gov.uk/downloads/file/3244/EconomicStrategy2021to2026.pdf

The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, vol. 12, Notes on Yorkshire Churches, p. 459: https://archive.org/details/yorkshirearchae11socigoog/page/n474

https://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ERY/HullHolyTrinity

The Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, Hull: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/east/vol1/pp287-311#h3-s3

Church of Holy Trinity: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1292280?section=official-list-entry

https://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ERY/HullStMary

The Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Hull: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/east/vol1/pp287-311#h3-s5

Church of St. Mary: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1217998?section=official-list-entry

The History, Antiquities, and Description of the Town and County of Kingston-upon-Hull quoted in Some Notes on St. Mary’s Church, Hull, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, vol. 24, pp. 275-285: https://archive.org/details/YAJ0241917/page/275

Drypool:

https://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ERY/Drypool

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drypool

https://opendomesday.org/place/TA1028/drypool

A History of the County of York East Riding: Volume 1, the City of Kingston Upon Hull, Drypool: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/east/vol1/pp460-464

Drypool, being the History of the Ancient Parish of Drypool cum Southcoates: http://79.170.40.245/drypoolparish.org.uk/drypoolparish/HistoryBook/index.php?$left=4&$right=5

Evidences Relating to the Eastern Part of the City of Kingston upon Hull: https://archive.org/details/evidencesrelati00clubgoog/page/n5

Drypool Church: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/east/vol1/pp287-311#h3-s6

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/River_Hull_tidal_surge_barrier

Marfleet:

https://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ERY/Marfleet

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marfleet

https://opendomesday.org/place/TA1429/marfleet

A History of the County of York East Riding: Volume 1, the City of Kingston Upon Hull, Marfleet: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/east/vol1/pp464-467

Marfleet Village: https://www.hull.gov.uk/downloads/file/3197/marfleet-village-appraisal

Marfleet church: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/east/vol1/pp287-311#h3-s8

Church of St. Giles: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1297039?section=official-list-entry

Sculcoates:

https://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ERY/Sculcoates

A History of the County of York East Riding: Volume 1, the City of Kingston Upon Hull, Sculcoates: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/east/vol1/pp467-469

Sculcoates church: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/east/vol1/pp287-311#h3-s10

Church of St. Mary, Sculcoates Lane: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1291590?section=official-list-entry

Sutton:

https://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ERY/SuttonOnHull

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sutton-on-Hull

https://opendomesday.org/place/TA1132/sutton-on-hull

A History of the County of York East Riding: Volume 1, the City of Kingston Upon Hull, Sutton: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/east/vol1/pp470-475

Sutton-in-Holderness, the manor, the berewic, and the village community: https://archive.org/details/suttoninholderne00blasrich/page/n8

Sutton church: https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/yorks/east/vol1/pp287-311#h3-s12

Church of St James the Great, Sutton on Hull: https://suttonandwawnemuseum.org.uk/history.html#st-james

Church of St. James: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1293238?section=official-list-entry