Brix, a small but strategically placed town on the Cotentin peninsula in the French province of Normandy, was the seat of the originally Scandinavian Bruce family that took its name from the town before finally settling in the British Isles in the wake of the Norman Conquest.

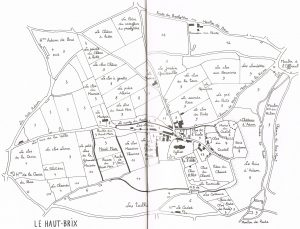

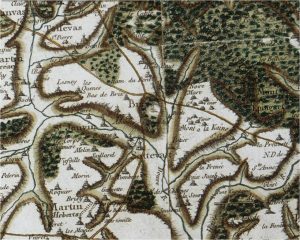

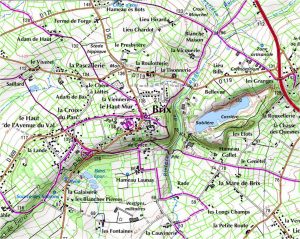

Traces of human activity have been found in Brix dating back 500,000 years, but the first remains of human settlement are from the Neolithic period. The Cotentin was at the time covered by dense forest surrounded by a narrow treeless coastal band which was punctuated by small inlets where early humans clustered. Rare paths criss-crossed the forest and where they met the trees were cleared, giving rise to inland settlements, mostly situated on high ground, of which the ancient centre of Brix, known as Haut-Brix (High Brix), is one of the best examples. Its western extremity is still known today as Haut Mur (High Wall), a reminder of how the most accessible part was defended. From there the prehistoric walls extended to the north and south, ending where the pointed spur of the hill on which the town developed overlooks a deep ravine, providing natural protection for its eastern extremity.

|  |  |  |

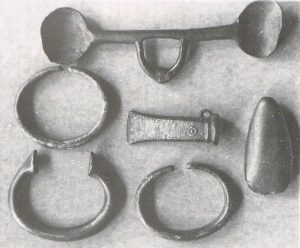

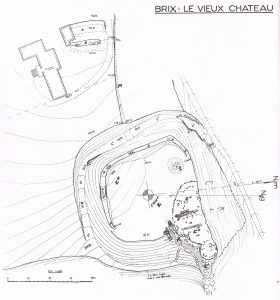

It was on this promontory that the Romans chose to build a castra exploratoria (a fortified and guarded administrative centre serving as a relay post). Abbot J.L. Adam states that the irregular square wall surrounding the camp was still visible at the end of the 19th century and that a number of gold coins were found on the site, two picturing Marcus Aurelius and one Nero. Subsequent excavations indicate that the medieval castle was built on the remains of the camp, probably between 1035 and 1050 during the troubled minority of William the future Conqueror, when fortresses were springing up all over Normandy. Sir Gabriel Jacques Surenne, a French born military historian who lived in Scotland and visited Brix in 1853, considered it to have been a first-rate fortress which only a large army was capable of taking. The site is now entirely contained in the grounds of the new manor house which lie to the north-east of the church. A ditch and mound (A and B) constitute the first line of defence at the entrance to the grounds, while the second is a rampart (D) protected by a 5m deep ditch (C) whose extremities end in the cliff, on top of which once stood a round tower (E’) and what appears to be a keep (E”). G marks the spot of a large vaulted room, now filled with rocks, and H a spiral staircase lying on its side. Within the enclosed area formed by these earthworks is a flat courtyard (E), which would have been a place of refuge for the townspeople, containing wattle and daub and wooden houses, a chapel and stables. On the south side of the courtyard are what appear to be either the remains of buildings built against the ramparts or the foundations of an ancient mound, now just a mass of masonry. Abbot Adam also provides a description of the underground passages, one of which (F) separates the courtyard from the keep and tower. He states that they led to an underground cave containing stalactites and that they had hidden exits, through which the occupants could flee into the surrounding countryside when attacked, but which have never been found despite the best efforts of the local schoolboys. Finally a funnel-shaped hole (I) marks the spot where excavations were carried out in about 1840.

|  |  |  |  |

Before pursuing the history of Brix, a word must be said about the evolution of its name. The Chronique de Fontenelle, drawn up between 747 and 753 in Latin, contains the first known written version of the name. It relates the story of the translation of the relics of St. George from Port de Ballius (Port-Bail) to a place called Brucius or Brutius, the description of which leaves in no doubt that the relics came to a halt at Brix, where the local count, Benehardus, built a chapel to house them. However, the name is said to be of earlier origin, from the Celtic word bruga or the Old Irish bruig, meaning bruyère (heather). Even this is disputed, though there is some agreement that the name is pre-Latin and therefore of ancient origin. A document written in c1000 under Richard II gives Bruet as the town’s name, and another written 26 years later under Richard III speaks of Bruscum. In 1042 under William the future Conqueror Brix is known as Bruis then, following the evolution of the language from Latin to French, variously as Brus, Briuz (1325), Bruys, Brye and Bris (1399) until Brix (pronounced bree) finally became the accepted spelling in the 17th century. The 46 charters of the priory of St. Pierre de la Luthumière (today part of Brix) show clearly the successive name changes.

The document from 1026 also makes the first known mention of the medieval castle. It describes the dower that Richard III of Normandy drew up for his betrothed, Adèle de France: “Je te concède…la cité qui se nomme Coutances, avec comté, sauf la terre de l’archevêque Robert. Je te concède aussi les châteaux qui s’y trouvent, à savoir Cherbourg, celui qui s’appelle Holmus, celui qui s’appelle Bruscum, avec leurs dépendances…” This provides documentary evidence that a castle already existed at Brix and that it was within the Duke’s domain. (Richard never actually married Adèle as he died in suspicious circumstances in 1027 and was succeeded by his brother Robert, who was in open revolt against him.)

Some historians believe that family that took its name from Bruscum were late arrivals in Normandy and that, like most latecomers, it had initially settled in the British Isles. There were two large waves of migration from Scandinavia. The first occurred under Rollo, who was also the first ruler (911-927) of the lands that the king of France conceded in return for an end to Viking brigandry, and the second during the rule of his great-grandson Richard II (996–1026). But the fact that the first known member of the family, Robert de Brus, was lord of a practically impregnable fortress, strategically situated in the middle of the Cotentin, and an important forest gives credence to Claude Pithois’s suggestion that he came from a junior branch of the Dukes of Normandy and was therefore one of the Duke’s trusted men. It is known that, after the death of Duke Robert, Robert de Brus remained loyal to his son William, while most of his peers were conspiring against the young successor.

Dives church, 2009

That a Brus accompanied William to Hastings is backed up by several sources.

John Brompton’s Decem Scriptores Angliae, lists:

Georges et Spencer

Brus et Botteler.

Wace in Roman de Rou et des ducs de Normandie speaks of:

Li archier du Val de Roil

A maint Engleiz crevèrent l’œil

Cels de Sole et cels d’Oireval

Cels de Brius et cels de Homez

De Saint-Jehan et de Brehal

Veissiez mult férir de prez.

Robert de Brix is listed on the plaque commemorating the Compagnons de Guillaume in Dives church and Bruce appears on the Roll of Battle Abbey.

During the 40 years between 1066 and the battle of Tinchebray in 1106, very little is known about Brix and the family from which its name is derived. French historians maintain that Robert had two sons, Adelme and Guillaume, but do not agree on which of the de Bruses accompanied William on his expedition*. Adelme in turn had sons with the names Robert, William, Peter, Adam and Richard, all of which appear with great regularity in the de Brus family. British historians are either in dispute or silent about this period, though George MacKenzie, Lord Advocate of Scotland, acknowledges the existence of Adelme and his son Robert in his manuscript of 1672 on The Scottish Nobility. This Robert, who became known as Robert I de Brus in England, was a favourite of Henry I and a staunch follower, as were many of his peers in the Cotentin. Robert probably played a leading role in the king’s victory over his brother at the battle of Tinchebray, having been promised or already received vast holdings in Yorkshire in return for his continuing loyalty. It can therefore be assumed that his brother Adam remained in Normandy as lord of Brix and that the medieval castle, the château d’Adam, and the road that crossed the town, the querrière d’Adam, were named after him.

It was the same Adam who built the church of Brix at the beginning of the 12th century. It stands on the highest point of Haut-Brix, probably on the remains of the chapel that had been built in the 8th century to house the relics of St. George, but which had been destroyed by the Vikings at the end of the 9th century. At the same time, on the instigation of Raoul, bishop of Coutances, he built the priory of St. Pierre de la Luthumière. According to Gallia Christiana Bishop Raoul had been moved by the miracles that had reportedly taken place in the church of St. Peter in Coutances which had presaged “punishment and vengeance” shortly before the battle of Tinchebray. It was he who influenced Adam to build a priory dedicated to the same saint, perhaps accounting for the ensuing naming of members of the Brus family Peter in both Normandy and England. Adam’s brother Richard held the office of bishop of Coutances during part of the time that the building of the church and priory took place. It is interesting to note that it was Adam’s nephew, the English Adam, who, according to Simeon of Durham, died in 1144 and who in the same year, no doubt sensing his own mortality, gave the church and priory to the Benedictine abbey of St. Sauveur le Vicomte, so that the monks would pray for his soul and that of his ancestors. Furthermore, the donation was confirmed in 1155 by Peter, son of William and grandson of its Norman founder, “with the consent of his overlord, Adam”, his English cousin, which indicates that the Norman family was subordinate to the English family.

There now ensued a period of calm during the long reign of under Henry II (1154-1189), but this was shattered during the reigns of Richard I and John by events that would lead to the eventual loss of Normandy by the English crown. Both Richard and John paid visits to Brix. In 1194 Richard the Lionheart arrived at Barfleur from Portsmouth with a large number of troops to relieve Verneuil. Etienne Dupont quoting Matthew Paris reports that he spent the night of 12 May at Brix castle: In festo sanctorum Nerei et Achillei apud Portesmuthi navem ascendens, in Normanniam appulit et apud Bruis nocte illa quievit. Similarly M. de Gerville quoting the Rolls of the Tower of London reports that King John spent the night of 24 September 1200 at Brix castle on his way back to England with his new bride, Isabelle of Angoulême. The murder of Arthur of Brittany marked the beginning of the end of Norman dynasty begun by Rollo, as Philippe-Auguste of France set about invading the provinces of Touraine, Anjou, Maine and Normandy. John, surrounded by overwhelming forces on all sides, withdrew from his capital Rouen to the Cotentin and finally set sail for England on 5 December 1203 from Barfleur. Once the French king had taken possession of Normandy in 1205, the lords of Brix were faced with the choice of swearing allegiance to France or England. It is claimed that the English barons sought a compromise, requesting permission from John to swear fealty to Philippe-Auguste so that they could keep their lands in Normandy: Vous aurez nos cœurs et le roi de France aura nos corps, but this was rejected. As the Brus holdings in England and Scotland were significantly larger than those in France, they chose the former. Later Louis IX ordered that the château d’Adam be dismantled – removal of its mantle (fortifications) – but not demolished. If the castle buildings were left intact, they suffered from the passage of time and their re-use as material to build the houses of the town and reconstruct the church. However, the fact that the foundations remain undisturbed means that any future excavations should reveal the exact lay-out of the castle.

The abandonment of Normandy by the Bruses would suggest that no member of the family remained in the province but, as was the case for many of their peers, the Brus family continued as two separate branches, with the name de Brix surviving to the present day in Normandy and with different arms from those of the English and Scottish branches. They were uprooted from Brix during the Hundred Years’ War and lived for a number of centuries in Montfarville, near Barfleur, until towards the end of the 19th century when Charles-Camille de Brix gradually started buying back the land of his ancestors. It was not until 1914 that work began on a new house on land beside the old castle; it was built in the style of Louis XV and became known as “Bruce Castle”. The house passed through two further generations of the de Brix family until it, all its contents and the grounds were eventually sold to Hugues and Anne-Rose Fontanet, who tend it personally with the respect due to a property that is able to draw on such a wealth of history.

Sources:

Brix, berceau des Rois d’Ecosse, Claude Pithois, 1980

De Normandie au trône d’Écosse : la saga des Bruce, Claude Pithois, 1997

Le Haut Mur et le Château d’Adam, Frédéric Scuvée, 1977

Le Château de Brix en Normandie, Etienne Dupont, in The Scottish Historical Review, volume 2, 1905

Recherches Historiques et Topographiques sur les Compagnons de Guillaume le Conquérant, Etienne Dupont, 1900

Le Château d’Adam Bruce à Brix, Abbot J.L. Adam, in the Mémoires de la Société Nationale Académique de Cherbourg, 1897: http://le50enlignebis.free.fr/spip.php?article13400

Recherche sur les anciens châteaux du département de la Manche, M. de Gerville, from the Mémoires de la Société des Antiquaires de Normandie, 1824

(de Gerville spent 10 years in England during the French Revolution)

Mémoires de la Société des Antiquaires d’Ecosse, vol. 1, Sir Gabriel Jacques Surenne, 1672

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compagnons_de_Guillaume_le_Conquérant

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Companions_of_William_the_Conqueror

http://midgleywebpages.com/battleroll.html (*Adam and Guillaume de Brix but no Robert)

http://www.robertsewell.ca/dives.html

https://www.wikimanche.fr/Brix#Toponymie

http://remparts-de-normandie.eklablog.com/les-remparts-de-brix-manche-a131028180

http://closducotentin.over-blog.fr/article-le-chateau-de-brix-forteresse-oubliee-du-cotentin-medieval-96271987.html

http://www.bruce-castle.com/histoire.php?lg=eng